Conway invited residents attending its Christmas tree lighting to use stickers to vote

on the park features the would like to see added or improved. Photo: City of Conway.

Creating a plan for a city’s growth, and enforcing the regulations that will help achieve the plan, is a job for experts in planning, architecture and development. Even so, a key ingredient for that plan is input from residents themselves.

Cities are actively engaging their residents in these planning processes to foster better outcomes, stronger community ties and greater public buy-in. The idea is to ensure that residents are well-informed about regulations and feel that the city is addressing their needs and their visions for what they want their community to be.

The City of Conway gets its community engaged in the master planning process through outreach.

Recently, it sought input on a new parks and recreation master plan during its annual Christmas tree lighting. Residents attending the event were given stickers by the master plan consultants they could use to vote on projects they wanted to see completed. The results of the vote will be used to prioritize projects that the city council will budget for and work could begin as early as this year.

“What our community sees is that we have taken these plans and they immediately go into action,” said June Wood, Conway’s public information officer. “We put them into the budget process and we get the funds for them. They immediately see the results of their buy-in, their comments, their feedback and that encourages further engagement.”

Community engagement is built into the planning process, said Mary Catherine Hyman, Conway’s deputy city administrator.

For parks and recreation planning, the city met with people and organizations who use or provide funding for parks, including a steering committee with the athletics director from the school district and an executive from Conway Medical Center. The city also has pushed online surveys through social media and handed out surveys to people using the facilities.

“You need to find out where your community is, and go to them and ask them what they want in a place that they are comfortable,” Hyman said. “We have tried to get people’s opinions where they were and didn’t ask them to come to us.”

Using that public input as a guide for project prioritization has led to the city updating plans that are as little as five years old because so much of the work identified in the public input process has been completed.

As projects are finished, the city also makes sure to highlight which master plan it was part of and what the public input was, Wood said.

“You have to celebrate your achievements as a city,” she said. “You make sure the stakeholders are aware and know that we are opening a project they were involved in.”

The City of Beaufort established a historical technical review committee to help residents

with changes they want to make on properties in the historic district.

For the City of Beaufort, which has a more than 300-acre historic district, helping residents navigate a detailed collection of historic preservation rules and regulations was a top priority for Curt Freese when he arrived to serve as community development director less than two years ago.

“It was taking some people like a year or more to do a simple project — everything in the city was having to go the historic review board, like for paint and things like that,” Freese said. “That small stuff can all be administratively approved now.”

He created a historical technical review committee that residents can approach for free advice on any changes they want to make to property within that historic district. The committee includes city staff, historic preservation experts and the private nonprofit Historic Beaufort Foundation.

“It’s good for them to be involved,” Freese said. “They have a lot of funding and try to save as many buildings as they can.”

Freese said the addition of the foundation was not popular at first, but the lack of issues since the creation of the committee confirmed for him that it was the right decision.

“I think it has headed off cases that they were concerned about,” he said. “When people feel part of the process they tend to be more accepting. Plus, they have a lot of expertise. They are long-time preservationists and they have some good takes on things.”

Residents can bring projects to the committee before they hire an architect or contractor. The committee gives its opinion of the project and of the details of the work to be done. Comments are recorded so everyone can know what the key issues are. The process can save residents thousands of dollars and months of time.

“There is so much subjectivity in architecture and historic preservation,” Freese said. “We’re trying to get a lot of opinions — expert opinions — and make it fully transparent.”

While the committee is available to anyone looking to do work on a building in the historic district, the goal is to help residents.

“The historic district can be so difficult,” he said, citing the need for approval from the Historic District Review Board for most projects and the city’s 300-page preservation manual.

“Developers that want to redevelop have the resources to hire architects and attorneys, the regular person that bought a house in that district and just wants to do something, that’s not only difficult, but expensive … So just trying to help them as much as possible is really to the benefit of everyone.”

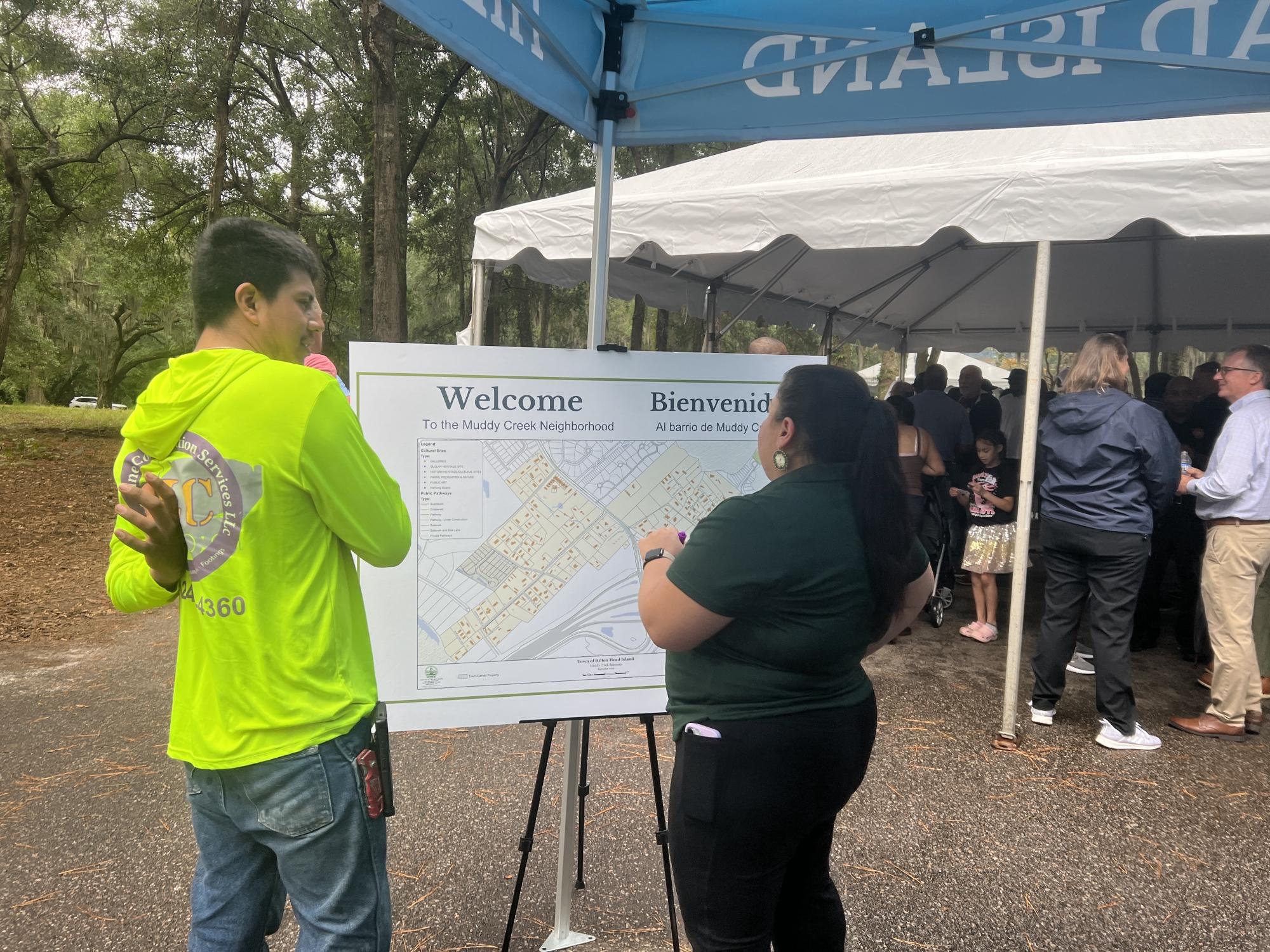

Last September, the Town of Hilton Head Island hosted a community event in the

Muddy Creek neighborhood to gain input on everything from roads to parks,

stormwater, sewer, permitting and public safety. Photo: Town of Hilton Head Island.

The Town of Hilton Head Island places community involvement at the heart of its planning initiatives, said Missy Luick, director of planning.

The town’s comprehensive plan was developed with extensive input from task forces and stakeholder groups, ensuring the goals and projects reflect community aspirations. The robust engagement has become a hallmark of Hilton Head Island’s planning approach. A recent series of meetings with the Muddy Creek area of the town has led to some action items the town could take immediately.

“We heard about the need for improved public safety. We heard that there was a lack of parks or open spaces and pathways within that particular neighborhood and that residents supported beautification efforts like tree trimming, landscaping and community cleanups,” Luick said. “We hosted a community cleanup event that was very well attended as a follow-up from our engagement effort.”

A second cleanup event was planned for early 2025 as well.

Other issues concerned flooding — an ongoing concern in coastal areas — and traffic — an ongoing concern for tourist areas.

Hilton Head Island and other coastal municipalities also must deal with creating affordable housing for their workforces, while still attracting retirees, part-time residents and tourists.

One of the town's unique challenges stems from the neighborhoods that operate under private covenants and restrictions, which account for about 70% of the island’s land. These communities often have their own architectural review boards that coexist with the city’s design review board.

To navigate overlapping regulations, Hilton Head Island collaborates with these entities to ensure all criteria are met. This layered system underscores the town's commitment to balancing autonomy with collective planning.

The rest of the island has been divided into eight planning districts, which like the Muddy Creek neighborhood are providing feedback on the status of current development and what the communities would like to see.

The town is using in-person meetings, mailed invitations and online surveys to reach as many residents as possible.

This inclusive approach extends to historically underserved areas, such as the Gullah Geechee communities. The town is working on a neighborhood stabilization plan, informed by input from these historic communities, to address housing and cultural preservation concerns.

“It's listening and just making sure that it's not the planning director's plan, it's got to be the community's plan,” Luick said. “I'm really excited to get out in the community and have these conversations and really get that gut check to make sure that what we've been putting together is truly what the community wants to see. And if it's not, then we'll recalibrate where we're headed.”